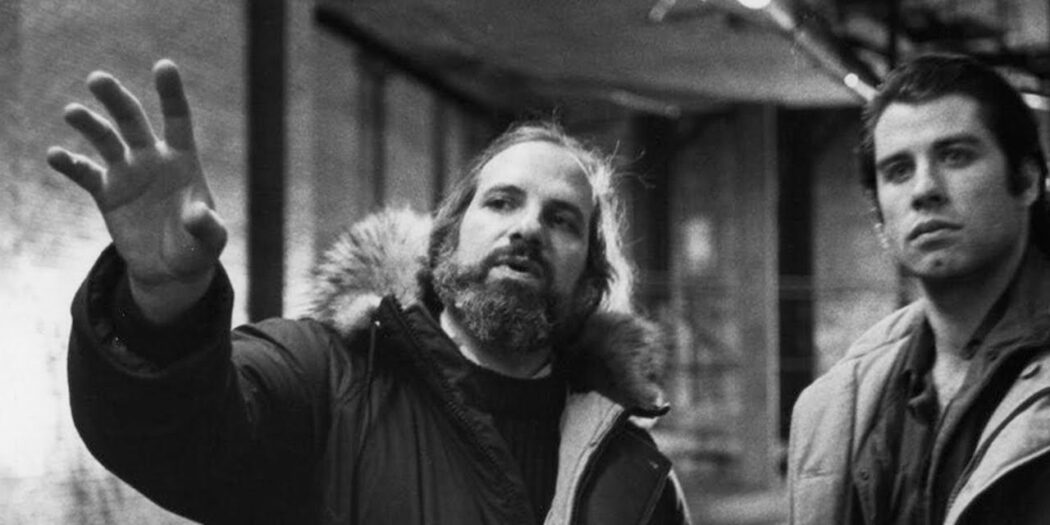

Though it’s a contentious subject, I believe mainly in the auteur theory – which is a way of looking at cinema with the director as the “author” of this work. It’s controversial because the film is one of the most notorious collaborative exercises one can get involved in. I don’t think the auteur theory disses the idea that cinema isn’t cooperative. Instead, it’s a theory that argues that a film reflects the director’s artistic vision. A movie directed by a particular filmmaker will have recognizable, recurring themes and visual cues that inform the audience who the director is. The French New Wave movement in the 60s popularized this. When you think of auteur theory, the number one director that comes to mind is Alfred Hitchcock, who the French New Wave and the Cahiers critics heavily championed. The career of Alfred Hitchcock had a significant impact on filmmaker Brian De Palma, who emerged out of the anti-war 60s with other New Hollywood figures like Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and Paul Schrader. These filmmakers were the first generation to go to film school and study film. They would go on to redefine Hollywood cinema. Of all those filmmakers, perhaps the most underrated impact has to do with De Palma.

One can’t mention Brian De Palma without first mentioning the controversies. He’s primarily known as a Hitchcock clone, with thrillers inspired by Hitchcock like Sisters, Obsession, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, and Body Double. However, simply dismissing De Palma as a Hitchcock clone is very misleading. True, films are primarily known for their graphic violence, sometimes against women, and their sexual content. However, De Palma was inspired by Jean Luc Godard and was a politically motivated filmmaker. You can look at his two early films: Greetings and Hi Mom. These two films examined female objectification and helped define how Americans understood the Vietnam War, racial unrest, and other issues of the day. Early De Palma might seem a strong contrast with his hypersexualized melodramatic thrillers of the 70s and 80s, but the two De Palma’s work hand in hand.

https://youtu.be/B98O4dbvRs8

De Palma is not a misogynist. The reaction to his violent pictures of the 70s and 80s was a reactionary movement of the time, not without some valid basis. De Palma’s pictures became prominent during the slasher era, with films like the Halloween and Friday the 13th franchise dominating the box office. These films did not have a sympathetic portrayal of women, but De Palma’s films are different. You just need to look at Sisters, Carrie, The Fury, Dressed to Kill, and Blow Out to see that De Palma crafts solid and sensitive women characters who are more than what they appear. Look at Dressed to Kill, for instance, a highly controversial film because of its portrayal of transgender as a murderer. Still, at the same time, Nancy Allen’s prostitute is presented as one of the picture’s heroes. Even when showing violence against women, it’s never anything but horrifying. De Palma argues that cinematic history is full of men photographing women, and that’s one of the appeals of movies. Why not? Everyone else does it. Advertising, paparazzi, media, and social media all revolve around photographing women.

De Palma’s most significant period of success was in the 1970s and 80s. Since then, he’s had mixed success and now, at age 82, does not make films as frequently as he used to. His last film was Domino (2019), and De Palma has expressed dissatisfaction with that project. Indeed, throughout De Palma’s career, he’s dealt with numerous production difficulties. Just look at The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), a film that’s more notorious for the production itself than the giant bomb it became. De Palma has often been at odds with critics and audiences, but decades later, he is finally being recognized as the great auteur he is. He’s fortunate always to have two significant champions of his work in the critical community, Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael. He’s also celebrated by modern-day filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, who his work has inspired.

So what are the auteur aspects of De Palma movies? It mainly comes down to the look and subject matter of the film. De Palma’s films can fall into two categories, his psychological thrillers (Sisters, Body Double, Obsession, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Raising Cain) and his predominantly commercial films (Scarface, The Untouchables, Carlito’s Way, and Mission: Impossible). Like many prominent filmmakers, he’s worked back and forth between the studio system and films that are more personal to him, aka “De Palma” films. De Palma’s camera shots are unique and known for unusual angles and compositions. He uses a split diopter to emphasize the foreground person/object while keeping a background person/object in focus.

The split diopter is one of my favorite movie shots, and filmmakers like Tarantino and Scorsese have used it as a homage to their friend De Palma. As a student of Hitchcock, De Palma is well aware that the build-up to the suspenseful moment is more important than the actual big moment itself. De Palma is known for long, sometimes unbroken, almost silent movie-type sequences. One only has to look at the fantastic sequence in Dressed to Kill in the art museum. De Palma loves allowing the audience to feel what the character is feeling. There’s the vicarious thrill that you’re eavesdropping on something you’re not supposed to see with the character.

De Palma is the undisputed king of cinematic set pieces, and where he truly excels is in self-contained cinematic moments. The opening scene of Snake Eyes, the long split-screen sequence in Sisters, the gallery scene in Dressed to Kill, the Eisenstein-inspired line on the staircase in The Untouchables, the chainsaw scene in Scarface, the race to Grand Central Station in Carlito’s Way, the final chase in Blow Out, the prom sequence in Carrie, the finale of The Fury, the death of Tran on the bridge in Casualties of War, the break into CIA headquarters in Langley in Mission: Impossible, the opening heist at Cannes in Femme Fatale. When you think of De Palma, you think of memorable cinematic moments. Scenes and images that stick with you for the rest of your life.

I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of De Palma’s impact on my cinematic life and cinema. I’m here to rank his ten best films. As a significant De Palma fan, this was a challenging endeavor. Still, I want to give newbies to De Palma a chance to appreciate what the director has brought to the cinema.

10. Mission: Impossible (1996)

In 1996, De Palma needed a hit badly, so naturally, he leaped at the chance to helm a Tom Cruise starring vehicle, Mission: Impossible. As a kid, I remember being significantly confused by the plot, but I’ve come to respect the first Mission: Impossible over the years. It’s complicated and gloriously shot. It’s an example of an auteur director elevating a director-for-hire assignment with elegant camera movements and sequences of amazing suspense like the break-in at Langley, the film’s centerpiece sequence.

9. Casualties of War (1989)

I wrote extensively about Casualties of War in my Unsung Cinema series. Decades later, the film now stands out amongst the flurry of Vietnam movies released then, which meant that Casualties of War seemed old hat by 1989. However, De Palma’s film is highly harrowing and anti-war. It’s not an easy watch, but it consistently makes you hold your breath from start to finish.

8. The Fury (1978)

The Fury is pure outlandish fun from start to finish. With great performances from Kirk Douglas and a sinister John Cassavetes, it’s also hard not to be won over by the bravura direction and exhilarating pace. The fantastic ending also helps and is incredibly cathartic. The Fury is everything, Cronenbergian science fiction, James Bond spy thriller, Hitchcockian suspense, and coming-of-age story. All of it works somehow.

7. Carrie (1976)

The film made De Palma a household name. His adaptation of Stephen King’s novel is frightening and memorable. It also features his first work with John Travolta and Nancy Allen, who would return for more De Palma films later. This film makes you feel the horror of high school.

6. Femme Fatale (2002)

An uncommonly elegant, witty, and sexy heist movie that features De Palma almost venturing into David Lynch territory, Femme Fatale is a wholly original piece of filmmaking that enraptures you from the very beginning with an exhilarating heist at Cannes. It’s all freewheeling and insanely watchable.

5. Carlito’s Way (1993)

Often regarded now as even better than Scarface, Carlito’s Way is the second fantastic gangster epic De Palma and Pacino made together. Unlike Tony Montana, Pacino brings a world-weariness to the role that makes you root for him. The star performance of this picture is Sean Penn as Carlito’s lawyer.

4. Scarface (1983)

A great American epic that I’ll defend any day of the week. Written by Oliver Stone, who brings authenticity and danger to the screenplay, and directed with operatic elegance by De Palma, Scarface is endlessly rewatchable. I’ll often throw it on just for specific sequences alone.

3. Dressed to Kill (1980)

Some of De Palma’s best work is in Dressed to Kill, including the very thrilling and erotic sequence at the art gallery, which has horrible implications later. Dressed to Kill is inspired by Psycho but carves out a place of its own, thanks to De Palma’s inspired giallo direction.

2. Body Double (1984)

Perhaps many De Palma fans won’t have Body Double ranked this high. Still, I think it’s an essential De Palma movie and his kind of take on Hollywood in general. It’s a film that encapsulates all the great things about De Palma, the entertainer, and provocateur. Like Hitchcock’s Rear Window and Vertigo, voyeurism is a vital part of Body Double, but that’s what movie watching is, voyeurism. De Palma knows this more than any filmmaker and puts the audience into the character’s point of view.

1. Blow Out (1981)

De Palma’s most complete thriller and best film, Blow Out, is completely enthralling from start to finish. It benefits significantly from the Philadelphia locales that create a moody atmosphere. The ending is gloriously downbeat and unforgettable. It’s John Travolta’s best performance as well.

Movie Finatics The Place for Movie Lovers

Movie Finatics The Place for Movie Lovers