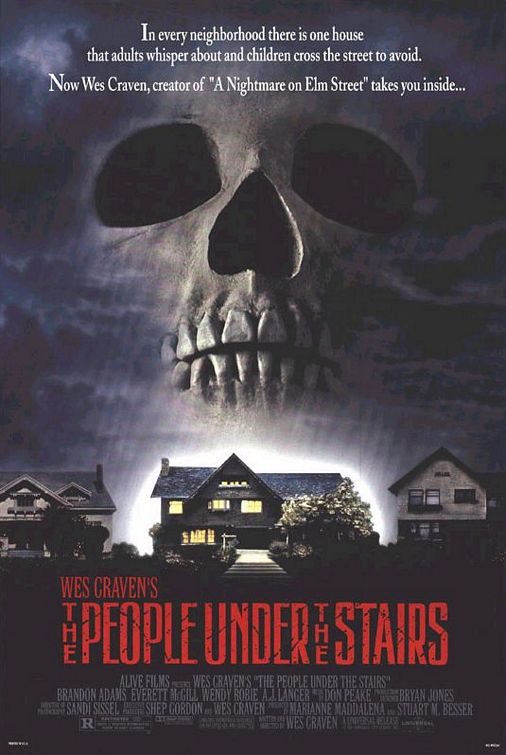

Wes Craven’s The People Under the Stairs is a masterclass in horror filmmaking that expertly blends chilling terror, social commentary, and riveting storytelling. Released in 1991, the film showcases Craven’s ability to create an atmosphere of dread while delving into thought-provoking themes. It does qualify for Unsung Cinema despite the film received good reviews and was a success at the box office. You can argue that in terms of unsung compared to other Craven films (also put The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) on there) and other horror films. It’s not an overtly political movie per se, but it critiques capitalist greed. The film explores the consequences of economic disparity and the lengths to which people are driven when they face poverty and eviction. The villains of the piece are appropriately white landlords who own the black lower-income apartment complex. Wes Craven is no stranger to horror films with social critiques like The Hills Have Eyes, Last House on the Left, or A Nightmare on Elm Street. The People Under the Stairs works cleverly as an urban and suburban horror satire—a house horror film where we’re rooting for the people who broke in.

The story follows a young boy named Fool (Brandon Adams of The Mighty Ducks and Sandlot fame), who lives in a poverty-stricken neighborhood. When his family faces eviction due to an unjust rent increase, Fool is approached by Leroy (pre-Marsellus Wallace Ving Rhames), a seasoned criminal, with a plan to break into the mansion of their wealthy landlords, the Robesons (Everett McGill and Wendy Robie), to steal a rumored treasure. As Fool and Leroy infiltrate the Robesons’ estate, they discover a horrifying reality within its walls. The mansion is filled with hidden chambers and secrets, and its inhabitants are subjected to sadistic treatment by the Robesons. Fool encounters the “people under the stairs,” a group of deformed and abused individuals who are held captive and exploited by the Robesons. As Fool navigates the treacherous corridors and evades the Robesons, he becomes determined to uncover the truth and free the captives. Along the way, he allies with a girl named Alice (A. J. Langer), who has also suffered under the Robesons’ tyranny, and a boy named Roach, whose tongue was extracted as a punishment for having called out for help to escape (thus breaking the “speak no evil” rule enforced by Mommy and Daddy) also dodges the Robesons by hiding in the walls. Together, they must outsmart the Robesons, survive the horrors within the mansion, and bring their crimes to light. The film intensifies as Fool and Alice uncover the mansion’s dark secrets, facing various dangers and encounters with the deranged Robeson. Their struggle for survival and justice escalates into a climactic confrontation that reveals the depths of the Robesons’ cruelty and the resilience of the oppressed.

The People Under the Stairs thrives on its examination of social inequality and abuse of power. The Robesons, played with a perfect blend of menace and derangement by Everett McGill and Wendy Robie (who reunite as a couple after playing Big Ed and Nadine on Twin Peaks), embody the upper class’s dark underbelly. They rule over their crumbling mansion (think of the frugality of Ebenezer Scrooge), with Craven comparing their depravity and increasing wealth, manipulating and tormenting those less fortunate. Craven’s screenplay cleverly uses the Robesons’ actions as a scathing critique of the privileged elite, exposing their cruelty and showcasing the stark contrast between their opulent lifestyle and the struggles of the impoverished. The characters of Mr. and Mrs. Robeson are multifaceted and complex, with McGill exuding an imposing presence and Robie oscillating between eccentricity and sadism. This dynamic portrayal further intensifies the terror and adds depth to the film.

Craven and cinematographer Sandi Sissel craft a dark, oppressive atmosphere that permeates every frame. The Robesons’ decaying mansion, with its labyrinthine corridors, hidden chambers, and macabre decor, becomes a character. Craven’s use of shadows, lighting, and camera angles creates a sense of claustrophobia and unease, amplifying the terror and suspense of the narrative. The production design and set decoration enhance the film’s visual impact, immersing viewers in the disquieting world of the story. It was shot on a relatively low budget for the time at $6 million with little to no studio interference. One of the most impressive aspects of the film is its ability to evoke visceral fear through practical effects and makeup work. Craven’s skillful direction shines through in the film’s pacing and tonal balance. He expertly builds tension, steadily escalating the sense of unease as Fool’s exploration of the house becomes increasingly tricky. Craven’s suspenseful music, unnerving sound design, and well-timed jump scares keep the audience on the edge of their seats, fully immersed in the chilling atmosphere. The film’s score, composed by Don Peake, complements the visuals and heightens the suspense, adding an extra layer of intensity to the viewing experience.

Furthermore, the performances elevate the film’s impact. Brandon Adams delivers a compelling portrayal of Fool, embodying the character’s resilience, resourcefulness, and determination. Adams infuses Fool with raw authenticity, effectively conveying his emotions and motivations throughout the film. The audience becomes emotionally invested in Fool’s journey, eagerly following his every move and rooting for his triumph over the evil forces at play. Everett McGill and Wendy Robie’s performances as the Robesons genuinely stand out. McGill brings a commanding presence to the role of Mr. Robeson, exuding a sense of menace and authority that sends shivers down the audience’s spines. Robie, on the other hand, embraces the manic and unhinged nature of Mrs. Robeson, creating a character that is simultaneously fascinating and terrifying. The chemistry between McGill and Robie is palpable, intensifying the dynamic between their feelings and heightening the tension on screen.

The People Under the Stairs is a visual and performance-driven triumph and a thematically rich and socially relevant film. Craven’s screenplay serves as a scathing critique of social inequality and the abuse of power. The Robesons, with their opulent lifestyle built on the suffering of others, represent the privileged elite who exploit and manipulate the marginalized. Through their actions, the film highlights the stark contrast between the haves and have-nots, shedding light on the systemic injustices that persist in society. Furthermore, Craven deftly weaves in elements of dark humor, providing moments of levity amidst the tension and horror. The humor serves as a means of critique, exposing the absurdity of the Robesons’ actions and underscoring the film’s underlying themes. This balance of tones adds depth and complexity to the narrative, humanizing the characters and enhancing the social commentary. In terms of pacing, Craven perfectly balances slow-burning suspense and intense, pulse-pounding sequences. The escalation of tension keeps the audience on edge, building anticipation for the terrifying revelations. The film’s runtime is utilized effectively, allowing for character development, atmospheric world-building, and the gradual unraveling of the story’s dark secrets.

The People Under the Stairs is a film that leaves a lasting impact on its viewers. Its exploration of social issues, masterful direction, powerful performances, and striking visuals solidifies its status as a horror classic. Wes Craven’s ability to craft a chilling and socially relevant narrative is a testament to his talent as a filmmaker. The film’s legacy endures as it continues to provoke discussion and reflection on the inherent inequalities and abuses of power that persist in society. The People Under the Stairs is a testament to Wes Craven’s mastery of the horror genre. It is a film that challenges and disturbs, taking viewers on a nightmarish journey filled with chilling performances, atmospheric visuals, and thought-provoking themes. The best thing you can say about any horror film or anything, in general, is that it’s still relevant today.

Movie Finatics The Place for Movie Lovers

Movie Finatics The Place for Movie Lovers