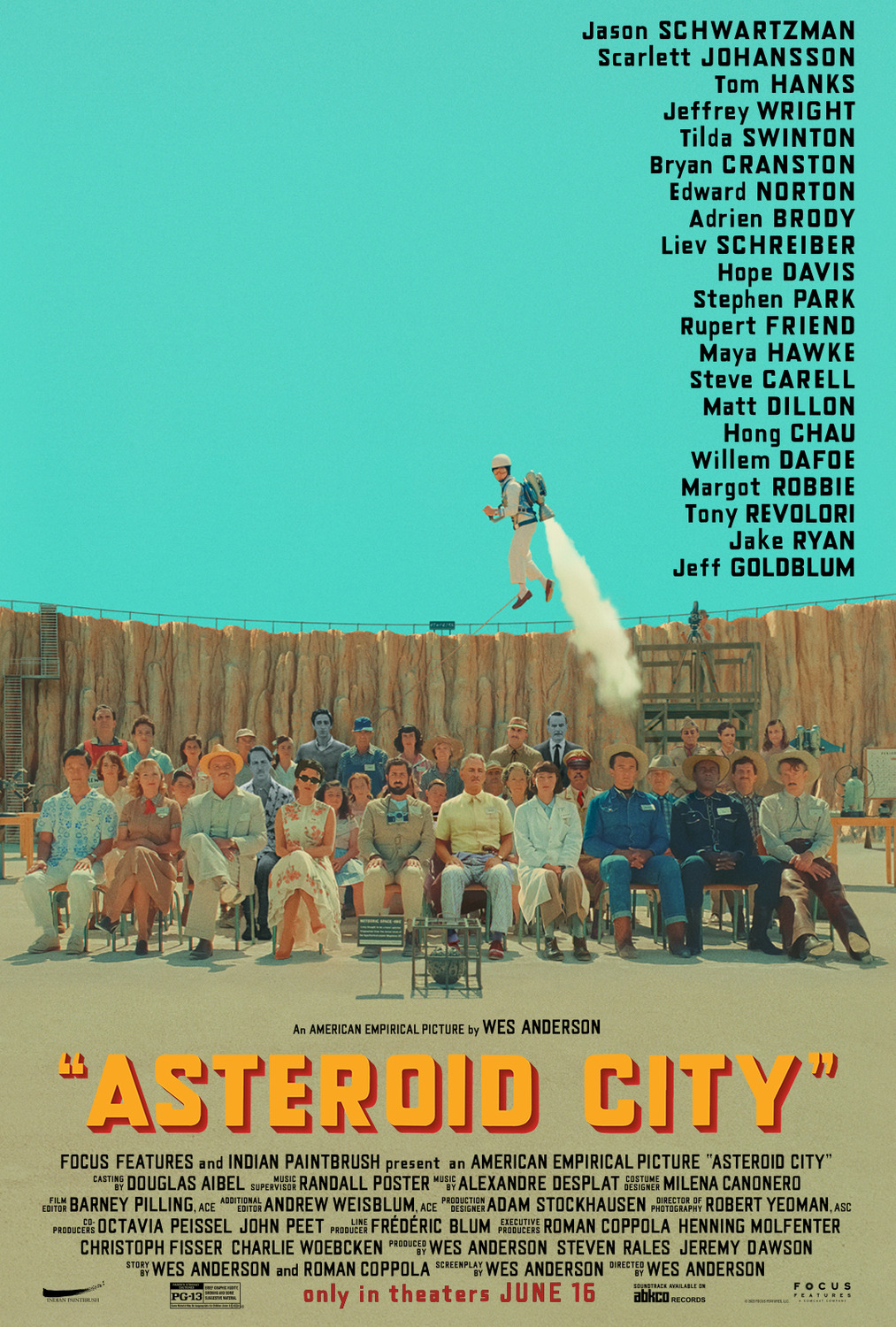

Wes Anderson is admittedly an acquired taste. He is known for his distinctive visual style and whimsical storytelling, creating films with eccentric characters and meticulously crafted aesthetics. There’s none like a Wes Anderson movie when you’re watching it. Everything in one of his shots is meticulously crafted down to the minute details. He prefers to work with lower budgets, usually from $15-$25 million. Asteroid City is perhaps his stagiest movie yet, which is no surprise because it’s a highly meta film about the stage. It’s also a love letter to cinema, like B movie science fiction. Characters modeled after Hollywood icons of the past like Marilyn Monroe, Stanley Kubrick, and Elia Kazan. Yet beneath all the colorful characters and typical Wes Anderson quirks is an actual message. This might be Anderson’s most contemplative film. Born out of the Covid-19 pandemic, Asteroid City’s central theme is “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” While it might not win over new Anderson converts, I thought it was interesting enough to warrant a recommendation.

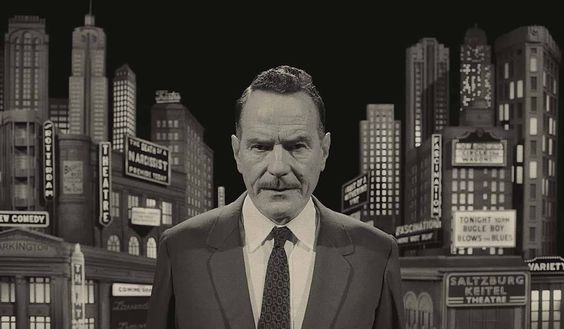

Set in a retro-futuristic version of the 1950s, a TV host introduces a televised production of (the in-universe fictional) Asteroid City, a play by famed playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton). In it, a youth astronomy convention is held in a fictional desert town of the same name. The play’s events are depicted in widescreen and stylized color, while the television special is seen in black-and-white Academy ratio. The televised production of Asteroid City commences with a TV host (Bryan Cranston) introducing the play, exuding a retro-futuristic 1950s vibe. The play’s narrative unfolds as war photojournalist Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman) arrives early at the Junior Stargazer convention with his intellectual teenage son, Woodrow (a superb Jake Ryan), and his three younger daughters. Augie’s car breaks down, prompting him to call his father-in-law, Stanley (Tom Hanks), for assistance. Despite their strained relationship, Stanley convinces Augie to reveal their mother’s recent death, which Augie had hidden from the children. As the story progresses, Augie and Woodrow cross paths with Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a renowned yet world-weary actress, and her daughter Dinah, who will be honored at the convention. Augie, Midge, Woodrow, and Dinah gradually develop romantic connections throughout the play.

For all the charges of Wes Anderson being a cold filmmaker (I don’t subscribe to that see Moonrise Kingdom), Asteroid City delves into the theme of grief and its processing. The character Augie and the actor portraying him have experienced significant life losses. The film’s play-within-a-play structure allows Wes Anderson to explore the meta-commentary on how artists, including himself, navigate grief by creating or engaging with art centered around loss. Jones, the actor, becomes frustrated as he anticipates finding definitive answers to the profound pain associated with grief through the play’s theme exploration.

However, the film acknowledges that sometimes there is no clear-cut reason for the loss and the accompanying anguish. While narratives surrounding grief can offer solace and the reassurance that others share similar experiences, they cannot entirely alleviate the pain or provide a satisfying explanation for suffering. Schubert, the play’s director, assures Jones that he must continue to tell the story even if he does not fully comprehend it. He affirms that Jones portrays the character correctly and encourages him to persevere. Like Augie, Jones must persist and keep moving forward. Eventually, both characters will find happiness again amid their grief.

In this exploration of grief, Asteroid City reminds viewers that the healing process is complex and does not always come with clear answers or quick resolutions. Art can provide a means of expression and connection, offering comfort in shared experiences. However, it cannot replace the individual journey of processing loss or provide an all-encompassing explanation for personal pain. Instead, the film suggests that finding solace and moving forward requires perseverance, an understanding that healing may be nonlinear, and recognizing that happiness can be rediscovered in time.

The film’s central statement, “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep,” can be seen as Anderson encouraging the audience to get lost in the power and escapism of art. The film suggests that life, akin to a grand show, should be embraced and performed wholeheartedly, even if there may not be a clear point or message. Anderson confronts this perceived lack of depth in his work by affirming that one can find meaning through doing, living, and performing. For that life is one big performance. There are also many quirky, funny side characters, like Steve Carell as a motel manager with various gadgets like a margarita vending machine. The whole subplot with an alien is fun, and the first appearance of it is genuinely enrapturing. Asteroid City might be too dry and meandering for some, but I was touched by the film’s unique exploration of the meta.

*** out of ****

Movie Finatics The Place for Movie Lovers

Movie Finatics The Place for Movie Lovers